The beginning of the end for Greenland’s last remaining ice shelves

A new study just published in Nature Communications, shows that Greenland’s last stable ice shelves have started to thin and disintegrate, accelerating the global sea-level rise.

In Greenland, most glaciers started losing mass in the 1990s. This happened specifically in the northwest and southeast part of the ice sheet, while the most northern part of Greenland remained stable. The glaciers located in the north are now the last glaciers in Greenland with large floating extensions. These floating extensions are called ice shelves, and play a crucial role as dams that suppress the flow from the center of the ice sheet. Once these ice shelves start to thin and fracture, the dams become weaker allowing more ice to flow into the ocean.

The weakening has now begun!

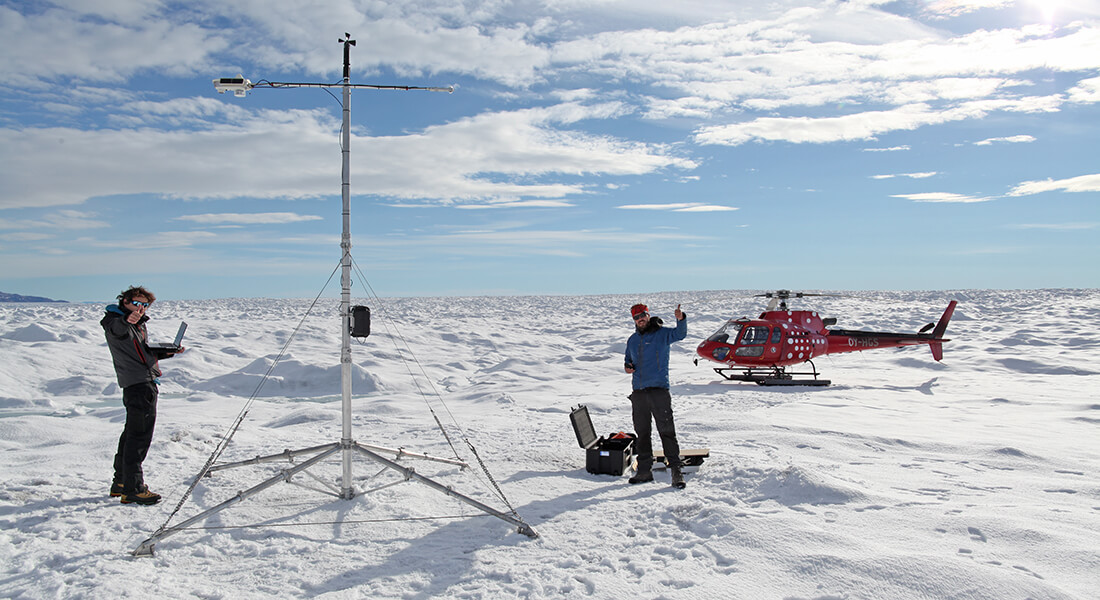

Researchers from Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management at University of Copenhagen in collaboration with French Colleagues from CNRS (IGE, Grenoble), and the National Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (Copenhagen, Denmark), have just published a study in Nature Communications which shows the first signs of weakening of these important glaciers. Using a large collection of satellite images, scientists calculated that these important glacier dams had lost more than a third of their volume recently.

The scientists observed for the first time that melting had drastically increased since the 2000s.

"When we first had the maps, we saw that the rates of underwater melting were incredibly high, reaching over a hundred meters of melt per year!", explains Romain Millan, who led the study while working at Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management at UCPH and Grenoble.

By using ocean temperature measurements collected over the past 40 years and comparing them with physical reanalysis, researchers determined that this increase in melting was largely due to significant warming of ocean waters throughout the region.

The group of scientists also measured the glacier flow and ice thickness, and calculated the amount of ice discharged into the ocean. For some glaciers, the discharge has increased by more than 25%. This means that more and more icebergs are being discharged into the sea, directly impacting sea level rise.

"Under current climatic conditions, polar regions will inevitably continue to warm at far too high rates",comments Romain Millan.

A continuous increase in air and ocean temperatures could therefore pose a long lasting threat to the last ice shelves in northern Greenland.

"If these ice shelves collapse, as has happened to neighboring glaciers, there is a real risk that this region could become the largest contributor to sea level rise in the entire Greenland ice sheet", concludes Anders Bjørk from Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management at UCPH.

In Antarctica, the majority of the ice sheet flows into the ocean from large floating platforms. The rapid changes observed in Greenland could thus be considered a first glimpse of processes that could affect Antarctica in the near future, with even bigger consequences for the global sea-level.

"We need to keep an eye out for Antarctica, and put our new methods to use there", says Anders Bjørk and adds “and luckily the Villum Foundation of Denmark has granted us money to develop these methods and to do just so”.

Please find the article in Nature Communications here

Photo: Shfaqat Abbas Khan.

Contact

Anders Anker Bjørk

Assistant Professor

aab@ign.ku.dk

+45 29 92 17 42

Anette Bill-Jessen

Communications Coordinator

anbj@ign.ku.dk

+45 93 51 13 70